(CNN) -- It was the most

ambitious and the deadliest terror attack since

the rampage by Pakistani militants through Mumbai five years ago. And

it raises the alarming prospect that al Qaeda affiliates and other

jihadist outfits could turn parts of northern and western Africa into

no-go zones -- places too dangerous for Westerners to work, or even

visit.

The attack on the In

Amenas gas facility left 37 foreign workers dead, according to the

Algerian prime minister. It showed that al Qaeda-linked groups now have

the resources to reconnoiter and launch complex attacks against places

far from their strongholds, using a network of camps and intermediaries

throughout the desert.

If their rhetoric is to

be believed, their goals include targets farther afield -- leveraging

sympathizers among the vast North and West African diaspora in Europe.

A spokesman for the man

who orchestrated the attack, Moktar Belmoktar, told French media Monday

that France would see "dozens like Mohamed Merah and Khaled Kelkal."

Merah shot dead seven people in Toulouse, France, last year; Kelkal

carried out a series of attacks in France in 1995.

Oil companies reassess risk

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algeria PM: Facility was booby-trapped

Algeria PM: Facility was booby-trapped

Family of slain hostage seeks answers

Family of slain hostage seeks answers

Obama's hostage crisis response

Obama's hostage crisis response

The most immediate

concern to counterterrorism analysts is that Belmoktar will launch more

attacks against Western companies in North Africa. A second attack on

oil and gas infrastructure could cause foreign oil companies to reassess

their exposure in Algeria, Libya and parts of West Africa, or at least

raise the security costs of doing business in the region.

A former head of

intelligence for the Transitional National Council in Libya, Rami El

Obeidi, told CNN last week that with the French intervention in Mali, "a

Pandora's box has been opened," and he believes oil fields in Libya are

also at high risk of being attacked.

Geoff Porter, a longtime

observer of events in North Africa, says a mass exodus of Western

companies from Algeria is highly unlikely. But, he said, "the Algerian

hydrocarbons sector will enter a holding pattern for the next month or

so, possibly resuming meaningful activity at the beginning of March."

"Companies looking at

potential opportunities in Algeria will now look not only at the

available acreage's prospectivity, but also how its location impacts

security concerns and associated costs," Porter added.

Belmoktar, the leader of

a newly formed Saharan al Qaeda franchise that split from al Qaeda in

the Islamic Magrheb (AQIM) last fall, remains at large, likely hunkering

down in northern Mali, where he is believed to have amassed weapons and

a war chest of millions of dollars from ransom payments and smuggling.

Belmoktar has been based

in or near the town of Gao, where endless tracts of desert as well as

cave complexes have been a safe-haven for a variety of militant groups

affiliated with al Qaeda since armed Islamist rebels drove out

government forces early last year.

Last month he announced the formation of a new commando unit called Those Who Sign with Blood.

"He has all the

resources he needs in terms of money, weapons and soldiers to launch new

attacks, and his recruitment and fundraising efforts will likely be

boosted significantly because of the attack," said Noman Benotman,

himself a former Libyan jihadist who is now a senior analyst at the

Quilliam Foundation in London.

Complex attack

Belmoktar became known

as "Mr Marlboro" because of his smuggling enterprises. But Robert

Fowler, a Canadian diplomat who was held for 130 days after being taken

hostage by Belmoktar in 2008, said he had no doubts about where

Belmoktar's priorities lay.

"His men were amongst

the least materialistic I ever encountered. His criminality always

served the expansion of jihad," he told CNN.

According to Benotman

and other sources, the leader of the Algerian attack was Taher Ben

Cheneb, the Algerian head of The Movement of Islamic Youth in the South.

In his 50s, Cheneb was a longtime associate of Belmoktar. Cheneb was

supported by Abdul Rahman al Nigeri, from Niger, and another Algerian,

Abou al Barra.

The unit Belmoktar

dispatched was well-armed: heavy machine guns, assault rifles,

rocket-propelled grenades, mortars and explosives were recovered from

the scene. And eyewitness accounts suggested the group or supporters had

undertaken advance surveillance because it was apparent the attackers

were familiar with the sprawling facility.

U.S. officials and North

African sources believe the attackers entered Algeria from Libya and

that some may have been trained in jihadist camps in southern Libya, not

far from the In Amenas gas facility. The sources tell CNN that Libyan

authorities are aware of three jihadist camps south of Sabha providing

instruction to militants from North Africa and the Sahara, but have

lacked the capability or will to move against them.

According to one source, Belmoktar visited the commandant of one of these camps on a trip he made to Libya in late 2011.

Benotman says the first

phase of the assault involved an attempt to hijack a bus carrying

Westerners as it traveled to the local airport. This would have required

advance knowledge of travel arrangements. Benotman told CNN that in the

view of regional security officials, the attackers likely received some

insider help -- they also knew which units at the facility housed

foreign workers.

Algerian Prime Minister

Abdelmalek Sellal said Monday insider knowledge was passed on by a Niger

national who had previously worked as a driver at the facility.

"If there was an 'inside

man,' then this has certain implications for due diligence and vetting

of employees at other oil and gas sites," according to Geoff Porter, who

runs North Africa Risk Consulting Inc.

The attackers' plan,

according to Benotman, was likely to take hostages from the bus across

the nearby border into Libya, although he said it is possible their

final destination could have been another neighboring country, such as

Mali.

But the intervention of

Algerian forces prevented their escape. The second part of the plan

appears to have been to threaten to kill the workers if the Algerians

tried to storm the complex.

"If the attack was a

genuine attempt to seize hostages, then this raises the likelihood that

there will be another attempt at another facility," Porter said.

"The same implications

apply if the goal was to destroy the facility. If, however, the attack

was a 'spectacular' aimed at raising the profile of Moktar Belmoktar in

the Sahara, which appears to be the most likely interpretation at this

point, then the likelihood of it being repeated is lower," he added.

A jihadist spring

The attack on the

Algerian compound involved fighters from across North Africa and the

Sahara, according to Algerian authorities, including from Egypt, Mali,

Niger, Mauritania, Tunisia and Algeria.

"Belmoktar's group in

particular appears to have evolved -- they've been able to attract a

more diverse group of foreign fighters than before, and that's a

reflection of how other jihadists see them," said Andrew Lebovich, a

Senegal-based security analyst.

Several other jihadist

groups have also expanded, including factions of AQIM, a hotchpotch of

jihadist militias in Libya, and the Nigerian militant groups Boko Haram

and Ansaru. A variety of North African and Saharan jihadists and even

some Nigerian militants appear to have received training in northern

Mali, according to Lebovich, with different groups in the region

"cross-fertilizing."

Sources monitoring the

security situation in eastern Libya say that, if anything, it has

worsened since the attack on the U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi in

September, with a series of assassinations and attempted assassinations

of security officials, many of which are blamed on Islamist militants.

Libyan authorities are

aware of several jihadist camps providing instruction to Libyan

militants and foreign fighters in the Derna and Benghazi region, but

have not had the firepower to move against them. According to Western

intelligence officials, a leading jihadist operating in the area is

Abdulbasit Azuz, dispatched to Libya in 2011 by al Qaeda leader Ayman

al-Zawahiri.

The Nigerian group Ansaru claimed responsibility for an attack that killed Nigerian troops heading to Mali on Sunday.

"We are warning the

African countries to (stop) helping Western countries in fighting

against Islam and Muslims or face the utmost difficulties," the group

stated. Last year, White House counterterrorism advisor John Brennan

warned that Ansaru was committed to transnational jihad.

Terrorism analysts

believe that following the Algeria attack and the French military

operation in Mali, these groups may be inspired to launch attacks

against Western interests in the region.

"Fighting against local

governments didn't help them. It didn't create the euphoria they needed.

But now they have this foreign element: an invasion, the West,

Crusaders giving them a sense of meaning and a cause in exactly the way

Osama bin Laden envisioned," Benotman told CNN.

In recent days, Benotman

said, hardline Salafist preachers across the Arab world have declared a

call to arms against the French military intervention, depicting it as a

foreign occupation.

Long-term challenge

Western governments are under no illusions regarding the challenges that lie ahead in the region.

"It will require a

response that is about years, even decades, rather than months, and it

requires a response that is patient, that is painstaking, that is tough,

but also intelligent," British Prime Minister David Cameron said

Sunday.

Although in the long

term the Arab Spring may discredit al Qaeda's violent ideology, jihadist

groups have taken advantage of political turmoil and the dismantling of

security services in North Africa to build up their operations.

Over the past two years,

al Qaeda has shifted its center of gravity from the

Afghanistan-Pakistan border region where it is under pressure from drone

strikes toward the Arab world, green-lighting the return of dozens of

Arab operatives to their homelands, according to Western intelligence

officials. The emergence of Syria as a new jihadist cause celebre has

further energized militants.

In announcing the

formation of the commando unit in December, Belmoktar had promised

attacks on Western interests in the region and the home soil of Western

countries if they moved against jihadists who had taken over northern

Mali.

The fact that some of

the attackers in Algeria were carrying Western identification -- two of

them were reportedly Canadian -- will raise concern that the group could

retask such recruits to launch attacks in the West.

Algerian Prime Minister

Sellal said Monday a Canadian national known only as Chedad had played a

coordinating role in the attack.

"French security

officials have publicly said for some time that they are especially

concerned that Westerners could come back from North Africa or the Sahel

to launch attacks," Lebovich told CNN. The Sahel is the area along the

southern edge of the Sahara.

So far, neither

Belmoktar's group nor any other al Qaeda faction in North Africa has

come close to launching a terrorist attack in Europe. Virtually all the

AQIM cells dismantled in Europe were focused on logistics and

fundraising rather than plotting terrorist attacks, according to

European counterterrorism officials.

Confronting this emboldened transnational jihad in north Africa is a daunting task, complicated by several factors.

One is the long-standing

lack of cooperation between North and West African countries. Algeria

and Morocco, for example, are rivals for influence. Another is competing

priorities among regional governments. Western diplomats tell CNN that

Nigeria, for example, is more concerned about the threat from Boko Haram

within than jihadist safe havens in Mali.

There is also the long

experience of operating in the desert that leaders such as Belmoktar

have, and the complex relationships between different and often

fractious groups.

Another factor is that

the United States has not developed the sort of intelligence

infrastructure in this region that it painstakingly built up in the

tribal areas of Pakistan and Yemen. In December, U.S. officials began

discussing with Algeria the possibility that it might acquire its own

satellite surveillance system to monitor terrorist movements in southern

Algeria.

Analysts warn that

however successful the first phase of the French operation in Mali, it

is likely to encounter challenges similar to those faced by U.S. and

British forces in Iraq as the campaign evolves.

"For months jihadists in

Mali have been preparing for a military intervention by creating a

network of hundreds of weapons caches and safe houses in the desert

where they've stored weapons, ammunition, and food and set up

communication channels," Benotman told CNN.

He said Belmoktar in

particular may be hard to track down. "He's a survivor -- he knows when

to go into hiding when necessary," he told CNN.

That's why French intelligence officials have dubbed him "The Uncatchable."

Negotiators continued to demand that Dykes surrender, but authorities say the situation remained ‘static’ Wednesday. He’s also suspected of shooting 66-year-old Charles Albert Poland Jr., a bus driver in Midland City, before taking a child as a hostage from the bus.

Negotiators continued to demand that Dykes surrender, but authorities say the situation remained ‘static’ Wednesday. He’s also suspected of shooting 66-year-old Charles Albert Poland Jr., a bus driver in Midland City, before taking a child as a hostage from the bus.

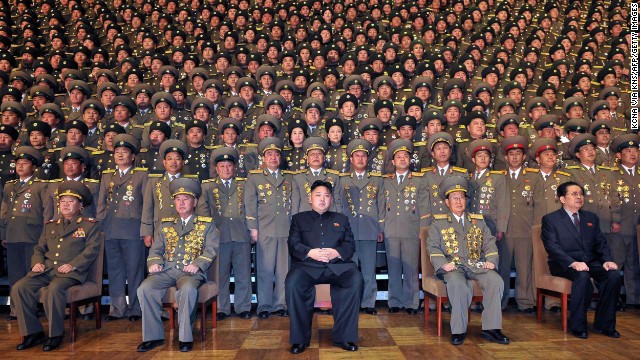

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un,

center, poses with chiefs of branch social security stations in this

undated picture released by North Korea's official news agency on

November 27, 2012. North Korea said Thursday that it plans to carry out a

new nuclear test and more long-range rocket launches, all of which it

said are a part of a new phase of confrontation with the United States.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un,

center, poses with chiefs of branch social security stations in this

undated picture released by North Korea's official news agency on

November 27, 2012. North Korea said Thursday that it plans to carry out a

new nuclear test and more long-range rocket launches, all of which it

said are a part of a new phase of confrontation with the United States.

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algerian PM: 37 hostages killed

Algeria PM: Facility was booby-trapped

Algeria PM: Facility was booby-trapped

Family of slain hostage seeks answers

Family of slain hostage seeks answers

Obama's hostage crisis response

Obama's hostage crisis response